L.G.C. Smith

This week marks the re-release of my first historical

romance, originally published by Avon Books in 1990. Now titled The Outlaw’s Secret Bride, it’s available

as an ebook from Amazon, Barnes&Noble, and Smashwords. TOSB,

a classic western romance set in the Black Hills of Dakota Territory in 1880, is

the story of an eastern schoolteacher who meets an outlaw she

can’t resist. She tries hard, but he doesn’t give up. I chose the setting

because my family is from South Dakota, and I made the heroine a teacher

because both sides of the family are chock full of South Dakota teachers. I had just started my doctoral

studies when I began writing The Outlaw's Secret Bride (originally titled Spellbound, and published under my pen name, Allison Hayes), so I wanted to be

practical. I figured writing about a place I knew fairly well would help me

manage the writing, the research it required, and a heavy course load.

Writing historical romance ended up shaping my academic work

in language education more than I anticipated. The tensions between the Lakota people

and the US government played out in many aspects of South Dakota history.

Education was a particularly fraught endeavor, illustrated in The Outlaw’s Secret Bride when the hero,

Drew, introduces Emily, the heroine, to Red Cloud, the famous Lakota leader.

Red Cloud astutely identified how disastrous the wrong sort of education could

be for his people. Thanks to the research for the novel, I began studying early

attempts to educate Lakota children. Red Cloud was right: the education brought

by white Americans relied heavily on coercion and the adamant rejection of

Lakota language, culture and values.

Occasionally educators, usually missionaries, developed

bilingual primers to help teach reading and writing to Native American

children. I discovered some of these buried in the University of California

library stacks and analyzed them for a research paper in the same year that

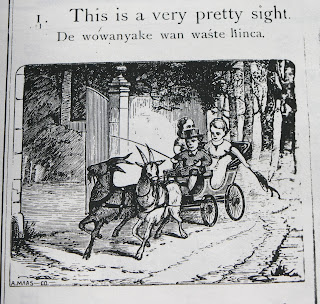

TOSB was first published. This is from a section looking at a little primer

called Model First Reader. Wayawa

Tokaheya. Prepared in English-Dakota by S.R. Riggs, an Episcopal missionary

to the Minnesota Sioux throughout most of the nineteenth century. It was

published in 1873 for use in western Minnesota. My interest lay in exploring

what Dakota and Lakota children might have been taught in schools using this

book. It serves as a back drop for understanding the kinds of conflicts my

teacher heroine encounters when she arrives in Dakota Territory and falls in

love with a man who has embraced the Lakota people.

An image of even more

cultural dissonance for Indian children than Howard and his sisters with their

pet goats appears a few pages later. On page 67 there is a drawing of a black

bear chained to a tall pole. The sentences are as follows:

1.

This is a black bear. De wahanksica heca.

(The normal gloss for bear is 'mato')

2. It is not a lamb. He tahinca cinca heca.

3. It looks ugly. He owanyang sica. ('Sica' means bad, not ugly

per se.)

4. He is chained to the pole. He can

kin en iyakaskapi.

5. Can he climb the pole? Can kin he adi okihi he.

6. Yes, he can climb to the top. Han, oinkpa hehanyan adi okihi.

7. I will not go near the bear. Wahanksica kin ikiyedan mde kte sni.

Aside from the alien

visual image of the chained bear, the words make it clear that the bear is to

be regarded as wild, potentially dangerous, and to be avoided by children. The

Dakota translation emphasizes that the bear is inherently bad and should be

handled accordingly. If it cannot be completely controlled, it must be avoided.

This is in marked

contrast to traditional Dakota perceptions of bears as the second member (the

other being humans) of the two-legged category of animals. Bears were thought

of as potential healers, teachers, and generally wise creatures. Dakota

children would have had to have been foolish not to have known that bears could

be dangerous (especially if unreasonably provoked by chaining them to a pole),

but they were taught a respect for animals, rooted in knowledge about their

behaviors, that is clearly lacking in this text. The image and the sentences

about the chained bear were very likely confusing for Dakota children because

they represented direct contradictions to traditional Dakota values.”

I have two nieces almost

finished with Kindergarten this year. Both are making great strides as

fledgling readers. It’s pretty easy for one of them, but not so much for the

other. I can’t imagine how hard it would be to learn to read from books that

had so little to do with their lives. A great teacher can work wonders with

almost any materials, but I wonder what the students who used these books

thought of them.

Reading is one of life’s

greatest pleasures for many of us. What were some of the first books you read

yourself? Were you one of the lucky people who just figured it out easily? (I

wasn’t.) Did you have a special teacher who helped you learn to read? Leave a

comment for a chance to win a copy of The Outlaw’s Secret Bride. I’ll draw a winner on Saturday, June 2nd

and post it here. Open to US and Canadian residents.

P.S. If you post a review

of The Outlaw’s Secret Bride to any

of the ebook retailers, email me the link at lgsmith@lgcsmith.com, and I’ll send you

a free copy of one of my other books.

.jpg)